Dr. Doug Sandle

EKPHRASTIC POETRY

Ekphrastic poetry (Ekphrasis) is poetry written to describe or to respond to a work of art. It is a Greek term and was originally poetry that described a work of art in detail. Friend and colleague Doug Sandle has written some ekphrastic poems in response to some of my paintings, in which he describes the narratives he sees in them.

The examples* below are part of a collection he is putting together entitled A Poetry of Seeing, which will also feature poems on artwork by internationally known artists, Patrick Hughes and Michael Sandle.

Scothall Drive

Here and now this scene leaks from our night dreams,

a still and lingering moment that has no beginning and no ending,

an empty silence locked into perpetual timelessness.

It is both dawn and dusk, a fading of light and a dying of dark,

a known and not known place prescient with a sense

of fear, and a loneliness that might have been,

and yet, always is.

A 63

We are lost, trapped in an everlasting tarmac of angst,

the cold screen of sky constantly rolling over

the always distant trees and deserted hedgerows.

The road cracks and shivers, there are no exits

or places for turning towards or back.

With Orwellian precision, the tall standing

lights survey and constantly track our journey

as an incessant booming refrain of dread

orders us, over and over, and yet again-

‘at the next roundabout keep to the road

and straight ahead.’

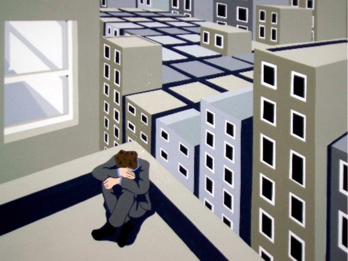

Buildings

He is on the edge, literally and emotionally,

contemplating a rushed fall and a speedy

down to earth death, freedom from the pain

of the anguish that harshly haunts

and consumes him.

He has recoiled, momentarily moved away,

sits frozen in fear, turns his back

Airport lounge

She sits in an empty and lifeless airport. No hordes or queues of eager or nervous passengers. Refreshment bars, arcade shops and cafés long closed, the once booming insistent tannoys now silent.

There are no crowded heartfelt goodbyes or welcome greetings.

She sits alone, her head drooping with a growing despair. A solitary noiseless airplane hangs in a cloudless sky about to land and unload her past, or to take off heavy with a cargo of her hopes and dreams.

She sobs, knowing that it will be there tomorrow, the next day, the next and thereafter.

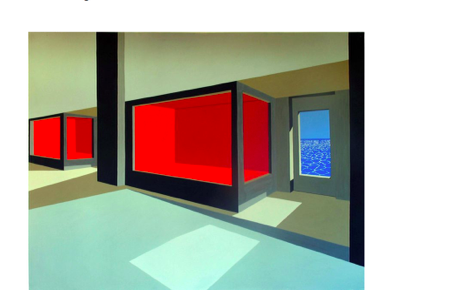

The giant vitrines reflect themselves,

the warm colours saturating their emptiness.

A noisy nothingness is left by whatever

once caught our consuming gaze.

Perhaps a display of exotic perfumes,

high fashion clothes, an arrangement of flowers

or even exotic foods from distant places.

But there are no shelves, no hanging pegs

no boxes, nor baskets. Just glimpses

of a mottled sea, and the slow

movement of a distant ocean.

Sometimes a sense of a presence

comes and goes, as the Dutchman Captain Hendrick ghostly walks

the freeboard deck, and whispers to the empty cabins below.

Published by Poetry and Covid – June 2021

The last class

It has been a difficult time and the teacher has exhausted

her telling of endless stories, the sharing of knowledge,

the changing histories, the mathematical magic

and the doings of good men and women.

She knows there will be grief and lamentations

and pain and sorrow among the geographies

of birth and death. But she also tells

of redemption and a teaching heeded

by those in near and distant lands

who will retell of her words and wisdom.

This Thursday of the last lesson, she raises her hand

to silence the babbling and prattling of her twelve

pupils, for there are final words to say,

to tell of a morning bird, a coming denial,

and of one who will betray.

Prof. Ruth Holliday, Professor of Gender and Culture University of Leeds (2018).

Art of Work.

Whilst others in this volume will pay more attention to the technical and artistic details of Paul Digby’s work, I will engage here sociologically with its content. What fascinates me about Digby’s art is the way it often takes ‘work’ as its object. His earlier paintings At Home and at Work illustrate some of the damage that bad work environments can do to us, creating stress, alienation and despair. It is hard not to identify with Digby’s vulnerable subjects bunkering under desks, or curled up in toilet cubicles. However, Digby’s more recent drawings extend these ideas into a particular climate of austerity and its impacts on public sector workers in the emergency services – services on which we all depend, sometimes for our lives.

Under successive Coalition and Conservative governments an ideologically motivated program of neoliberalism manifest as austerity has imposed cuts to the state on a staggering scale. Between 2010 and 2017 total public sector employment fell by 416,000, from 5.64 to 5.28 million. This means 15,000 fewer teachers in secondary schools, nearly 20,000 fewer police officers and 12,000 fewer fire fighters, making us less safe on the streets and in our homes. Violent crime is spiraling and the tragic loss of life and homes in the Grenfell Tower fire offers a devastating reminder of what can happen when we put cuts before safety and profits before people – even in London’s richest borough. Low pay and poor working conditions have resulted in 10,000 vacancies in the NHS. Nurses are using food banks to feed their kids.

But these cuts could only happen through a shift in our values. Cuts to public services accompanied a plethora of news stories about ‘lazy’ junior doctors and GPs who didn’t want to save lives on the weekend, teachers and lecturers with their ‘gold plated pensions’ and cushy hours, uncaring nurses neglecting elderly patients and corrupt police overreacting or burying evidence. In reality, these stories betrayed the effects staff shortages – each nurse covering swathes of patients, single police officers attending violent crime scenes alone – yet Daily Mail headlines excelled in turning the public against their ‘servants’.

But there is also a broader shift in the way we value work, captured in Digby’s Art of Work. Back when my grandfather mined coal in South Wales he was a ‘wealth creator’. He mined coal to heat homes and power industry. It was hot, dirty, dangerous work and despite losing three fingers in an accident he earned enough to pay the rent on his Coal Board house and feed his children without state benefits. In those days wealth was created by people who did the labour and their wages covered living costs, tax, and national insurance in case of sickness or unemployment and to support state services. Now it is the company bosses and hedge-fund managers who are seen as ‘wealth creators’, who cannot be taxed without pushing them abroad, for their talents to be snapped up by some other nation. But if rich people cannot be made to pay taxes, for fear they may move abroad, then we cannot afford the services of the state.

Anthropologist David Graeber argues that in modern consumer society working too hard has become a valued ethic, a kind of ‘secular hairshirt’, the sacrifice we make to be able to enjoy the pleasures of consumerism. People who find their job rewarding, therefore, are a problem. The logic of our modern consumer society is that the more a job is orientated to helping others, the less it needs to be paid, because helping others is rewarding in itself. Accordingly teachers shouldn’t teach for the money but for the love of instilling learning. Government schemes like Teach First follow this logic when they reconstitute teaching as a kind of voluntary pay back to society before graduates start a ‘real’ job in the city. So, under this ethic, the more useless (or ‘Bullshit’) a person’s job the more they should get paid [1].

Whilst paramedics and firefighters and police officers and university lecturers are being cut back to the bone, the number of people employed to monitor their activity has grown and grown. Bosses get bonuses for cutting the people that actually do the work, but they also need people working for them to make them look important. The more staff they have the more powerful their empire seems and the higher their executive pay should be. Bureaucrats in the private sector are hired to make rich people feel important and good about themselves, whilst bureaucrats in the public sector make poor people feel bad about themselves, monitoring the work of people who don’t need to be monitored and cut their benefits.

Digby’s drawings of public sector workers are truly remarkable. Each portrait takes around four months to compose and devotes meticulous attention to technical equipment, uniform, posture, embodiment and expression – not of landowners or of CEOs, or even celebrities – but of public sector workers in the emergency services. Digby’s art calls out and celebrates the people who work every day to save our lives and our homes, the people whose rewarding work makes them fit only for pay and job cuts in the age of austerity.

The drawing ‘Louise’ figures a woman firefighter, fully equipped, adorned in protective clothing, yet adopting a classic Madonna-Child pose, cradling an infant in her arms. Before the enlightenment art’s purpose was to represent the divine. The beauty of the artwork was supposed to ignite beauty and truth in the hearts of its spectators. Art was not for galleries or for collectors but inscribed into the fabric of religious buildings, humbling congregations with God’s divinity [2]. Mary occupies an ambiguous position. She is both mother of the divine, yet not divine – excluded from divinity by her womanhood. The Madonna is celebrated as a mother, yet also reduced only to motherhood. Women are exalted, but only when occupying desexualized and maternal roles, the passive ‘object’, rarely subject, of art. That Digby creates his Madonna-Child as firefighter and training mannequin infant is hugely significant. Digby’s Madonna is active worker rather than passive object. Her relationship to the infant is hero/ savior not mother. But whilst she protects she also cares. And this can tell us much about the value of women and the value of work.

As socialist feminists have demonstrated women’s work is erased from history [3]. We have come to think of work as men’s business. Since the industrial revolution divided labour along gender lines, men left the home and entered the office or the factory whilst women’s work was confined to the home – albeit often other people’s homes. Women’s domestic labour for their own and upper class families, became redefined as non-work. As ‘care’. Yet care work is often poorly rewarded. Graeber claims that whilst care work is devalued it is really the most important part of any job. He gives the example of tube workers criticized in the press for being lazy, numerous and replaceable with automation. Their union argued automated systems are fine until you lose your children, or your briefcase, or a fight breaks out on a train. It is the care work performed by rail workers that is vital, not stamping tickets. Women’s caring work, then, is the basis for thinking about the value and importance of work. Jobs in the public sector, and emergency services in particular, are jobs that look after people. They are more worthy of the attention and care that Paul Digby gives them than traditional portraits of landowners. His paintings on paper also show the desolation and alienation faced by those in ‘Bullshit Jobs’. But most strikingly his firefighting Madonna illustrates our way forward – a re-evalution of jobs based on caring – for each other and those who come next.

Notes

1. Graeber, D (2018) Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, Allen Lane.

2. Holliday, R and Potts, T (2012) Kitsch! Cultural Politics and Taste, MUP.

3. Silvia Federici (2010) Wages Against Housework, Caring Labour: An Archive, https:// caringlabor.wordpress.com/2010/09/15/silvia-federici-wages-against-housework

Dr. Doug Sandle (2006)

Paul Digby and the Metaphysical

Paul Digby graduated from Norwich school of Art and Design in 1997, and although his work has developed away from his earlier student interest in three dimensional sculpture and installation, his articulation and exploration of the spatial and our relation to it continues to be a thematic concern in his two dimensional work. His most recent gouache work uses the motif of a simple three dimensional house shape (rather like a monopoly house), which is variously placed in relation to its spatial surroundings through changing viewpoints, different forms of perspective and a fluidity between the exterior and interior. That such is sometimes the subject of different framed views, reminiscence of the multi-screen monitors of a surveillance camera, ensures that his exploration of space is dynamic in its articulation of the relationships among self, object and location.However if this dynamic quality appropriately describes Digby’s formal analysis, the use of flat painterly surfaces and a graphic quality often combined with a seemingly distant horizon, imbues the imagery with a sense of stillness and timelessness. It is this sense of infinite timelessness, a phenomenological distillation of a sense of present, future and past, which gives his work a psychological edge where space is not just a geometric or surface space, but an entopic space – the space of mental imagery and dreams*. Digby’s house-like objects, their walls and windows and the landscapes in which they are sometimes situated inhabit an environment that is metaphysical in the De Chirico sense of otherworldly, enigmatic and with a surreal sense of imagined timelessness,

*Digby also acknowledges the influence of comics and computer games on this series of work. Comic images are often instilled with memory and nostalgia, and the virtual space of computer games has an otherworldliness that contributes to its fantasy or dream-like quality.

To some extent Digby’s house-like object can be thought of as a device such as De Chirico’s use of statues, arches and chimneys in creating his metaphysical landscapes, but as well as external objects, Digby’s work often refers to rooms and their interior components such as walls, windows and doors. Such interior spaces are usually empty and bare, creating an existential nothingness to contribute to the overall enigmatic quality. The sense of nothingness and timelessness in much of Digby’s two dimensional work may relate to his past interest in Buddhism, and he recalls how during meditation he used to ‘focus on abstract shapes during meditation and they would float high in the void of my mind’ (Digby 2006a) – a confirmation perhaps of the entopic origin of some of his imagery. In his Axis entry Digby reflects on nothingness, the void and emptiness, and significantly on the enigmatic aspect of trying to define nothingness. He writes (Axis 2006), ‘The paradox is how can you define nothing; because memory cannot define nothing as the memory is memory, so define nothing!’

Yet within his work there is within emptiness a presence, which perhaps is one engendered by a felt unease or even angst.

Such is particularly strong in The Light, a painting with a title reference to the name of a shopping and entertainment complex in the centre of Leeds. However, while The Light complex was a conscious source of initial reference, the nature of light as depicted in the work and its spiritual connotations only serves to underscore its strong metaphysical presence. The painting depicts a flat painterly floor surface that slopes to meet the wall of a room or corridor, against which is situated a large display case. The vitrine is empty except for a luminescence and haunting red light that fills the cabinet but is contained within it. The vitrine and the red light are further reflected in what appears to be a mirror on an adjacent side wall. On the other side of the cabinet there is an open window that depicts what appears to be a distant sea. The whole scene is done from a single viewpoint that emphasises the linear perspective of the room and the cabinet. The location and its relationship to the sea are undefined and ambiguous – the sea could be a distant view or the room space could be located within a ship. The emptiness of the room, along with the sea and its distant horizon creates an enigmatic timelessness reinforced by the empty vitrine and its mirror image. The whole scene, both linearly and in the use of colour, is beautifully balanced with an aesthetic presence that adds to the dream-like and meditative nature of the work.

Digby’s interest in rooms and the spaces defined by walls and floor surfaces are evident in a number of works and projects over recent years. As an artist in residence to mark the closure of at Highroyds psychiatric hospital, Digby worked with the reminiscences of others who had experienced the hospital to use the interior walls of the empty hospital as a ‘metaphor for being inside the mind’ (Digby 2006b). He used the walls and corridors as mural surfaces on which to depict realistic images, such as of a mounted fire extinguisher, or a window grill, – motifs which served to both decorate the walls and play with and intensify the institutional nature of the environment. His interest in the hospital continued though using photographs of the deserted corridors and wards as a source material for a series of drawings, although also using memory to explore his own personal response to the hospital environment. Unlike the hospital corridors depicted by Catherine Yass or Damien Hirst, whose use of photography and new media are explicit within the images produced, Digby’s rooms and corridors are executed in a traditional looking style with heavy black graphite that give them a Piranesi reference. These inscapes also have a metaphysical quality, and while Digby sees them to some extent as places of refuge, they have none the less an ominous and disturbing presence, lifted only by the depiction of light and its illuminated surfaces. The crack which gives the title of one of these drawings shows a dark threatening split appearing in a corridor floor of an Escher like environment. The interplay between dark and light again seem to imbue the work with a spiritual presence, and the light provides some reassuring quality that Digby regards as more pertinent within this series than the otherwise potentially oppressive darkness of the graphite used to depict the images. In writing about this, Digby (2006a) recalls a repeated phrase, ‘you bring light into a dark space’, which features in a piece of music by Underworld. The concept of light in relation to dark has both metaphorical and personal connotations for Digby, which again refer to his past interest in Buddhism. That these inscapes are also metaphors for the mind is suggested by Digby’s comments that the objects and shapes depicted had for him an archetypal presence (Digby 2006b).

Digby’s graphic skill, mature sense of colour and his expertise in manipulating the picture surface are the result of conscientious research, as evidenced by a series of drawings and sketches done during 2000 -03. In this body of work the picture surface, object and expressive techniques are extensively explored and the foundations of later visual concerns and particular motifs are clearly established with energy and inventiveness. The seriousness with which Digby takes his artistic concerns is matched by his commitment to the application of art for social and individual well-being. As someone who has benefited from the therapeutic aspects of creative practice within his own development, Digby brings his skills and experiences to work with others, for example, his work with the homeless, with those with mental health problems, his artist residency at Rampton and his role in the Mind Odyssey movement. Digby (2002, p. 20) advocates that ‘art can represent or make real mental processes that are painful or traumatic. This may be in a representational way of something that has happened, or in a symbolic way giving personal meaning and expression to and mastery over mental processes’. In his most recent work, the house object, which he sees as archetypal of domesticity, is sometimes located in various spatial juxtapositions to a forest like environment. The forest he sees as a metaphor for isolation and as he comments, “I work with people that are isolated though living in vast forests metaphorically speaking….the work is to do with isolation and mental illness” (Digby, 2006b). In this series of work, the house and its setting are not only devices for articulating the spatial dynamics of the relationship between the three dimensional and the flat surface, but are metaphors for the human condition, – for the interplay between a self constructed domesticity and an uninhabited, potentially engulfing and agoraphobic ‘other’ world.

If Digby’s aesthetic concerns are metaphysical, his commitment to the application of art for social and individual development is firmly placed within the real world and the exigencies of everyday experience. It is his concern for such dualities; the spiritual within the physical environment, the present within a sense of timelessness and the metaphysical applied to the everyday, combined with skilful technique and sensitivity that give to his art both creative maturity and aesthetic quality.

Dr. Sue Wilks (July, 2008)

Hoping Against All Hope: A response to Paul Digby’s Artwork

Feelings that arise and thoughts that are formed in response to an encounter with any artwork can only ever be subjective. Individual viewers will bring to bear on each viewing experience their constituent influences: emotional, professional, physical, educational, cultural and so on, together with often-conflicting feelings and ever changing moods and memories. In other words the stuff of lives being lived. I was reminded of these subjective dynamics, not in a consciously and critically self-reflexive sense, but through the direct physical response I experienced the first time I looked at the drawing/painting, City,[1] produced by Paul Digby. Although the personal experiences that generated this physical (gut-wrenching) response to City are significant in the context of my own personal life stories, they are not important to detail in this text. To do so would be to reduce both experience and aesthetic activity to literal and symbolic translation, rather than to engage with these through creative thought processes. The physical response itself (as a trace element of my subjective experiences), however, can be useful because it provides me with a point of entry into thinking about City,

What emerges from City and the 2008 series of drawings/paintings that situate this artwork is, for me, a profound sense of struggle that is connected with the everyday difficulties people face as an outcome of the socially, economically, politically and culturally discursive forces that continually re-form and re-focus their lives, and also with the struggle to find meaning in life. This is not to suggest that there is a distinction between the struggle to physically survive and the struggle to find meaning in life, because minds and bodies operate interrelationally, not in an oppositional or independent manner.

This sense of struggle permeates both the 2008 series and earlier pieces, such as Corridor, 2004 and Bedroom, 2005.[2] There is some consistency of image content throughout; interior and exterior architectural spaces, entrances and exits, light, closures and openings, but unlike the earlier works, the 2008 series gives form to human presence and emotion. Human presence is evident through absence in the earlier works, (because of course there would be no architecture, environment, landscape and so on without human intervention) and emotion is implicit to the content, but it is not rendered in an explicit manner.

Both the 2008 series and the earlier artworks I refer to articulate the timelessness of human emotions and of the need to find enduring meaning in life. In particular there are references to contemporary situations, events and ideologies that people have been subjected to in UK society during the past three decades, (and indeed are complicit with enabling to come into being). I’m referring here, for example, to political and industrial drives to generate ever-increasing profit margins, global conflicts and to the audit culture that objectifies and represses human subjectivity, all of which generate feelings of confusion, frustration, distress, alienation, isolation, failure and so on.

Writing about Paul Digby’s artwork the psychotherapist, academic and writer Doug Sandle comments, ‘(…) in focusing on current world events alongside enigmatic interiors in his recent paintings, he relates contemporary experiences to timeless human emotions’.[3] Material issues and concerns will alter through; time, space, culture, geographical location, economical and political imperative and power regimes, but human emotions endure (Digby has previously stated that concepts of love and loss are intrinsic to his practice).[4] The artist seems to be engaged in a struggle to hold on to the hope and belief that there is more to life than that which is directly experienced… a life whose certainties include death, oppositional difference, suffering and oppression. This sense of hope and belief in something beyond-what-is radiates through Paul Digby’s depiction of external light sources, or saturates the surfaces of his artworks via the luminosity of pigment. He renders this unknown, intangible and elusive sense of hope with the same kind of solidity and physicality as the spaces that situate it.

And so, while I perceive a sense of struggle and despair in these artworks I also perceive a sense of belief and hope. Hope, belief, longing and desire are inscribed in human emotion and concepts of love and loss. The 2008 series of drawings/paintings, for me, resonate with the desire to know something that can only be felt, and frustratingly, not at will. Intrinsic to this desire is a commitment to a belief in meaning, love and ethics… not as fixed truths, but as damaged, contradictory and ever shifting concepts.

[1] Paul Digby, Axis, the online resource for contemporary art, available online, <http://www.axisweb.org/seCVPG.aspx?ARTISTID=5718> (accessed 21 July 2008).

[2] Paul Digby, Axis, the online resource for contemporary art, available online, <http://www.axisweb.org/dlFULL.aspx?ESSAYID=109> (accessed 21 July 2008).

[3] Doug Sadler, Axis, the online resource for contemporary art, available online, <http://www.axisweb.org/dlFULL.aspx?ESSAYID=109> (accessed 21 July 2008).

[4] The following quote is cited from a webpage that is no longer available. It was accessed online 21 July, 2008. On this page Paul Digby stated, ‘[M]y work is about portraying fundamentals found in the everyday by capturing the timeless feelings and thoughts that everyone experiences of love and loss’.

Dr.Krzysztof Fijalkowski

Joyland

Joy. Few other words in the English language seem so blithe, so uncomplicated. Knowing its origins reveals little: gaudere in Latin (‘rejoice’), then the old French joie. We normally look to the grain of a word, to its double meanings or unexpected backstory, to get a feel for the texture of its concept. We want shadows, something dormant and unexplained that will give us a grip on it as we turn it over in our hands and examine it from every side. But this time, nothing . . . pure joy, sheer happiness.

This is joy’s mystery: its purity, no hidden emotion, no otherness. And by the same token, from the outside – watched by envious onlookers – it appears to lack almost any defining feature (‘all happy families are alike’, writes Tolstoy in Anna Karenina), any geography, beyond a fuzzy and pastel-hued rapture. It is only experienced from within, cannot truly be shared and once finished – like some emotional wasabi – is largely lost to memory, just as this writing can circle joy’s geometric perfection but offer no plausible descriptions.

Never a mask, it effaces all other states if only for an instant, paints itself across the wearer’s demeanour. Head up, eyes wide, feeling leaks out uncontrollably to meet what the body should otherwise resist. The face opens out in smiles, the chest broadens its gait, perhaps the mouth falls open: open to the world, to a slow bolt of pure sunlight that bleaches out every dark tone with an intensity free of calculation or value. For a moment, as joy unhooks us from cares and the burden of reason, everything is connected and radiant: pleasure is crowned king for a day.

Of course, joy would have none of this majesty were it not that we long for it in the face of tedium, oppression or despair. Nietzsche, for instance, sees joy as the ultimate human state, one that is precisely the overcoming of unhappiness or pain. A life-affirming principle, the special province of art in particular, joy absorbs suffering, turns it into power. It is this quality that, for the philosopher, gives joy a tragic quality (‘deeper still than grief’ says Zarathustra), something profound, beyond either pleasure or sorrow and through which the individual may begin to re-align the world.

But could we really live in a state of permanent joy – forgo the doubled nature of the world for an ideal of harmony and elation against which nothing else can be the measure? The French phrase joie de vivre promises most nearly to express this apparently impossible notion: life professed in the face of everything that should tell us otherwise, a well-spring of optimism impregnable against everyday cares. Again, an impulse of sweeping away, of the stunning absence of disappointment or dark, but now prolonged into a spirit of vitality that wants to turn everything in its path to pleasure.

You might find the promise of happiness extended far into the distance in a constructive form in a place such as Joyland, on the seafront of Great Yarmouth (there are Joylands around the world: Texas, Kansas, Shanghai, Lahore . . .), an island of tourist amusement since 1949. Little funfair rides, sideshows, an arcade: it’s bottled and gaudy, naturally, but there’s still something about this brand of joy that feels close to its truth: transient, intense, temporarily but completely ignoring the world beyond its limits. A world of props and flats, of things gaily painted and colourfully out of kilter. While the children shriek with pleasure the grown-ups look on, sceptical or indulgent, sensing something missing in their own inability to be taken in. Here’s a reminder that joy is above all watched over by the realm of childhood, one to which adults long to return but that for the most part they may only glimpse, always out of dimension.

The revelation of joy is its replication of an instant of the unfathomable state of our earlier life, a time when each thought, each emotion eclipses all that has gone before, with no cares for that unfolding thing that might come next. Like a line of gunpowder, it sparks and leaves nothing, perhaps just a faint line that traces the route of an intimate apocalypse.